Death, Redemption, and Spiritual Transition in Medieval Thought: Purgatory, Revenants, and Mortality (12th–15th Century)

Introduction

The medieval period was deeply concerned with mortality, the afterlife, and the moral implications of death (Binski, 1996). Central to this discourse was the concept of purgatory, an intermediary realm where souls underwent purification to atone for sins (Le Goff, 1984). This theological framework gained prominence in the 12th and 13th centuries, bridging divine justice and mercy and offering hope for redemption (Le Goff, 1984). Alongside purgatory, the figure of the revenant—a corporeal returner from the afterlife—emerged as a counterpoint, representing unresolved moral debts and anxieties about death’s impermanence (Caciola, 1996).

Literature, theology, and art shaped how medieval society understood purgatory and revenants. Dante’s Purgatorio vividly illustrated the soul’s transformative journey, while frescoes such as the Last Judgement in the Church of St. Thomas à Becket reinforced purgatory’s moral significance (Lawrence, 2016). At the same time, revenant tales warned against spiritual negligence and improper burial rites (Caciola, 1996). This essay explores how these two constructs reflected medieval beliefs about decay, redemption, and spiritual transition.

Purgatory: Divine Mercy and Repentance

Purgatory emerged in Christian theology as a place of temporary purification for souls who had not fully atoned for their sins in life (Le Goff, 1984). It represented a middle ground between salvation and damnation, reconciling divine justice with the possibility of redemption (Le Goff, 1984). Thomas Aquinas (1265–1274) described purgatory as a “cleansing fire,” emphasising its role as a refining process rather than a punitive measure (Summa Theologica, II-II, Q.10). The doctrine provided medieval Christians with hope, reinforcing the idea that death was a transition rather than an end (Schell, 2024, pp. 21–23).

Medieval art and literature reinforced purgatory’s role in salvation. Dante’s Purgatorio depicted the soul’s gradual ascent through various levels of purification, reflecting the moral order of divine justice (Dante, Purgatorio I.4-6). Frescoes in churches, such as the Last Judgement in Salisbury, depicted purgatorial suffering, serving both as religious instruction and moral warning (Lawrence, 2016). These artistic and literary representations shaped medieval attitudes toward death, reinforcing the necessity of repentance.

Medieval Depictions of Purgatorial Torment

The portrayal of purgatorial suffering was designed to be pedagogical, stressing the importance of moral accountability (Le Goff, 1984, pp. 51–53). The flames of purgatory were described in sermons as a refining fire that prepared souls for divine union (Le Goff, 1984, pp. 51–53). Rituals such as prayers for the dead and indulgences reflected purgatory’s communal dimension, highlighting the interconnectedness of the living and the deceased (Schell, 2024, pp. 35–37).

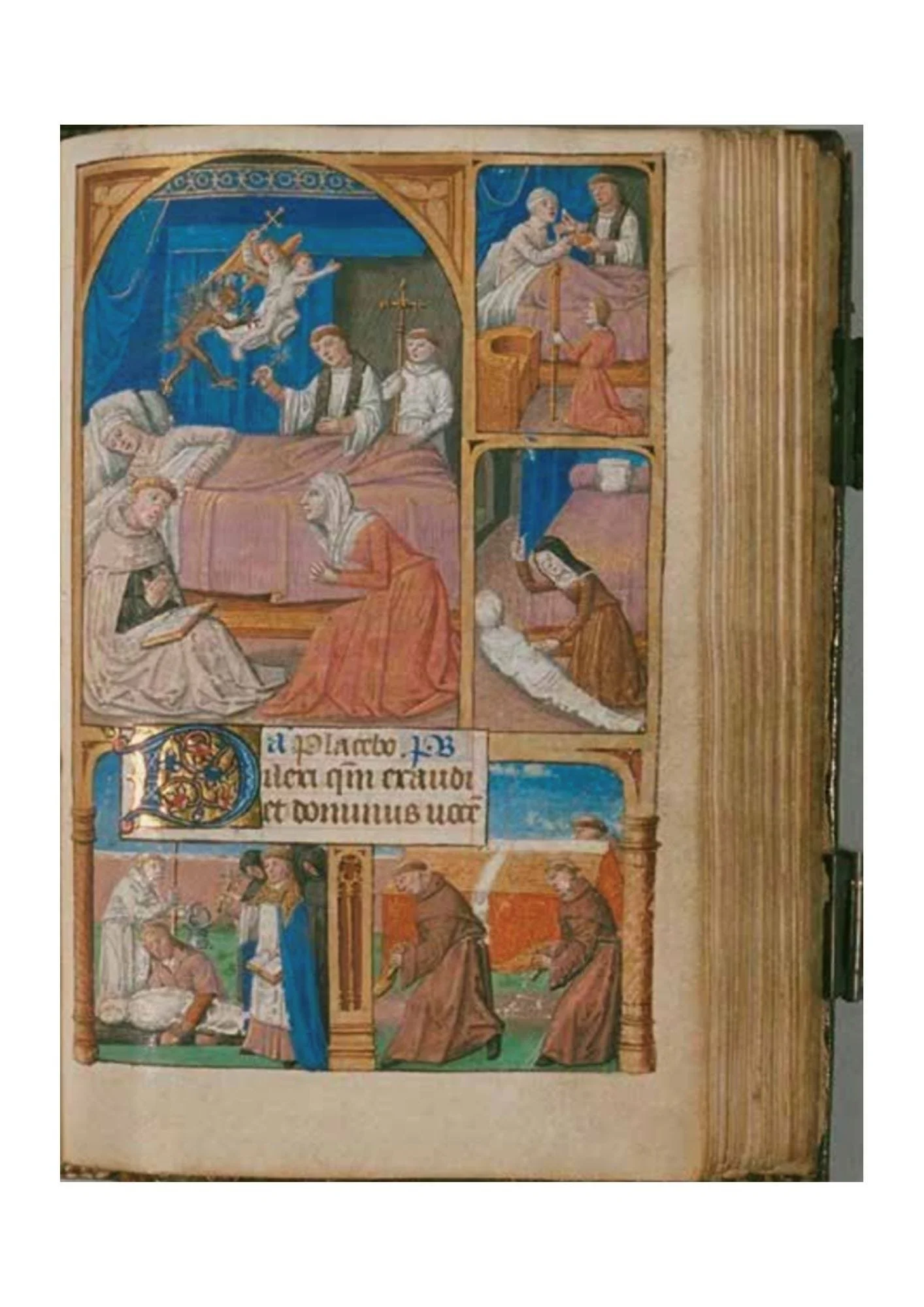

Figure 1: MS BP.96, Hours, France (Paris), 1475–1500, fol. 133 (Schell, 2024)

Books of Hours often included imagery of purgatory alongside prayers for the souls of the departed (Schell, 2024, pp. 35–37). These visual depictions reinforced the belief that suffering in purgatory was temporary and ultimately redemptive. The Office of the Dead, a liturgical text, contained meditations on bodily decay, underscoring purgatory’s role as both a place of atonement and a stage of spiritual transition (Schell, 2024, pp. 48–50).

Revenants: The Restless Dead and Spiritual Debt

Unlike purgatory, which offered a hopeful vision of posthumous purification, revenants represented a more ominous aspect of medieval eschatology. These corporeal spirits returned from the grave, often as a consequence of unresolved sins, improper burial, or divine retribution (Caciola, 1996). Unlike ghosts, revenants were tangible and often grotesque, embodying both physical decay and spiritual unrest.

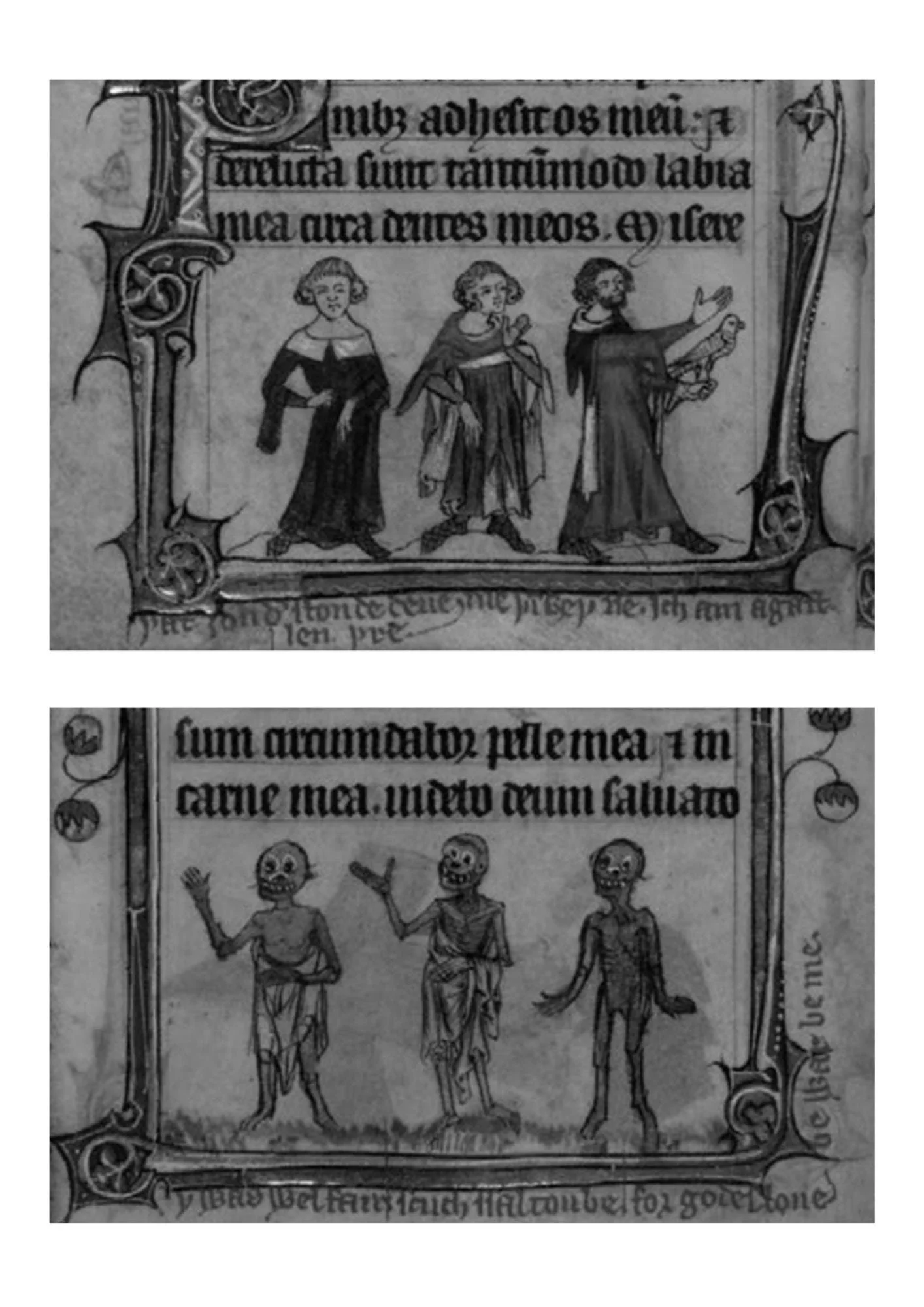

Medieval chronicles such as Historia Rerum Anglicarum and Gesta Danorum recount tales of revenants rising from their graves to terrorise communities (William of Malmesbury, c. 1125; Saxo Grammaticus, 1894). These figures reflected anxieties about moral transgression and the failure of burial rites to secure spiritual peace (Caciola, 1996). In The Taymouth Hours, an illuminated manuscript, revenants are depicted confronting the living as stark reminders of death’s inevitability (Schell, 2024). Such narratives reinforced the importance of proper burial and spiritual vigilance.

Figure 2: Yates Thompson MS 13, ‘The Taymouth Hours’, fols. 179v–180 (Schell, 2024)

Revenants often functioned as cautionary figures, serving both as agents of divine justice and symbols of moral failure. Their return underscored the belief that death was not an absolute separation from the world of the living but a liminal state in which the dead could still exert influence (Caciola, 1996). In some cases, revenants sought reconciliation, mirroring purgatory’s theme of atonement.

The Intersection of Purgatory and Revenants: Decay and Impermanence

Purgatory and revenants both reflected medieval concerns with decay, impermanence, and the afterlife. Purgatory’s process of purification mirrored the physical decomposition of revenants, suggesting that both the soul and the body were subject to divine justice (Caciola, 1996). Texts like the Office of the Dead blended themes of spiritual purification with meditations on bodily dissolution, reinforcing this connection (Schell, 2024, pp. 48–50).

Despite their differences, both purgatory and revenant tales highlighted the ongoing relationship between the living and the dead. Prayers and indulgences could aid souls in purgatory, just as the proper burial of revenants could prevent their return (Le Goff, 1984). In this sense, both constructs underscored medieval beliefs in the permeability of the boundary between life and death.

Cultural and Literary Representations of Death

Beyond theology, purgatory and revenants influenced broader cultural and literary depictions of death. Dante’s Divine Comedy transformed purgatorial doctrine into a vivid allegory of moral ascent (Dante, Purgatorio V.133–136). Similarly, medieval revenant tales functioned as moral lessons, warning audiences about the dangers of sin and spiritual negligence (Caciola, 1996).

Medieval art frequently juxtaposed purgatory’s suffering with revenant hauntings, creating a visual dialogue between spiritual purification and corporeal decay (Gertsman, 2020). These artistic representations engaged audiences on both an intellectual and emotional level, reinforcing the idea that death, though painful, was an essential part of the journey toward redemption.

Conclusion

Medieval conceptions of purgatory and revenants reveal a deeply interconnected understanding of mortality, morality, and the afterlife. Purgatory, as a site of divine justice and mercy, provided a framework for spiritual purification, as articulated by Aquinas and Dante (Aquinas, 1265–1274; Dante, Purgatorio V.133–136). In contrast, revenants embodied unresolved sin and the consequences of spiritual neglect, serving as cautionary figures in medieval narratives (Caciola, 1996).

Both constructs emphasised the transitional nature of death and reinforced the belief that the living and the dead remained spiritually connected (Le Goff, 1984). By exploring these dual frameworks, this essay highlights how medieval society sought to navigate the tension between decay and redemption—an enduring concern that shaped medieval and later perceptions of death.

References

Barber, P. (1988). Vampires, Burial and Death: Folklore and Reality.

Baxter, R. (1834). The Certainty of the World of Spirits.

Booth, P. & Tingle, E. (eds) 2020. A Companion to Death, Burial, and Remembrance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe, C. 1300-1700. BRILL, Boston. Available from: ProQuest Ebook Central. [10 December 2024].

Caesarius of Heisterbach. (1228). Dialogus miraculorum.

Caciola, J. (1996). 'Revenants: Corporeal Returners from the Afterlife,' Journal of Medieval Studies, 14(2), pp. 12–26.

Caciola, N. (1996). 'Wraiths, Revenants and Ritual in Medieval Culture,' Past & Present, 152(1), pp. 3–45. doi:10.1093/past/152.1.3.

Caciola, N. (2018). Afterlives: The Return of the Dead in the Middle Ages. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Davidson, H. E. and Fisher, P. (1979). The Gesta Danorum. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer.

Doré, G. (1857). ‘The Avaricious, Adrian V, Purgatorio Canto 19 verses 130-132’. The Divine Comedy.

Fein, S. G. (2014). ‘Life and Death, Reader and Page: Mirrors of Mortality in English Manuscripts,’ Studies in Iconography, 35, pp. 70–85.

Gertsman, E. (2020) The Invention of the Medieval Corpse: Body and Soul in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Gordon, S. (2018) ‘Dealing with the Undead in the Later Middle Ages’, in Tomaini, T. (ed.) Dealing with the Dead: Mortality and Community in Medieval and Early Modern Europe. Leiden: Brill, pp. 97–129.

Gordon, M. (2018). Medieval Folklore and the Dead: An Analysis of the Legend of the Three Living and the Three Dead.London: Routledge.

Gordon, S. (2018). ‘Dealing with the Undead in the Later Middle Ages,’ in Tomaini, T. (ed.) Dealing with the Dead: Mortality and Community in Medieval and Early Modern Europe. Leiden: Brill, pp. 97–129.

Guazzo, F. M. (1601). Compendium Maleficarum.

Horrox, R. (1994). The Black Death.

Lawrence, D. (2016). Doom or The Last Judgement. Salisbury at the Church of St. Thomas à Becket.

Le Goff, J. (1984) The Birth of Purgatory, Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Saxo Grammaticus, trans. Elton, O. (1894) The History of the Danes. London: Nutt. Davidson, H. E. and Fisher, P. (1979) The Gesta Danorum. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer. Taillepied, N. (1587/88). A Treatise of Ghosts.

Robin Kirkpatrick (trans). (2012). Dante, The Divine Comedy, Inferno, Purgatorio, Paradiso, Penguin Classics. ISBN 978 0 141 19749 4.

Rollo-Koster, J. (2017). Death in Medieval Europe: Death Scripted and Death Choreographed. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

Saxo Grammaticus, trans. Elton, O. (1894). The History of the Danes. London: Nutt.

Schell, S. (2024). Image and the Office of the Dead in Late Medieval Europe: Regular, Repellent, and Redemptive Death.Amsterdam University Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/9789048544233.

Taillepied, N. (1587/88). A Treatise of Ghosts.

Figure List

Figure 1: Schell, S. (2024) Image and the Office of the Dead in Late Medieval Europe: Regular, Repellent, and Redemptive Death. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/9789048544233 (Accessed: 17 December 2024).

Figure 2: Schell, S. (2024) Image and the Office of the Dead in Late Medieval Europe: Regular, Repellent, and Redemptive Death. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/9789048544233.