Materiality of Regenerative Architecture and Necessity of Decay

Introduction | 10-13 minute read

McDonough’s Cradle to Cradle presented a “simple, ground-breaking new vision” (McDonough, 2011) of design and materiality. This vision, inspired by the biological cycle of decay and renewal, established a manifesto to use fewer and less material and to utilize material available in circulation through a circular system. McDonough proposed that materials should be designed to be perpetually recyclable, ideally within a closed-loop system that mimics natural processes. However, this approach fails to fully engage with the inherent biology of materials. By focusing on recycling and repurposing, it removes decay from its natural context and imposes a somewhat artificial cycle on materials. If we comprehend material as a living entity, where decay is not just a final stage but a regenerative and responsive process, how would architects’ approaches to design change?

When working with organic materials and craft techniques, architects and designers interact with the intrinsic properties and behaviours of materials, fostering a deeper understanding and relationship. This engagement with materiality can lead to a more nuanced approach to design that embraces the dynamic nature of materials rather than viewing them merely as static objects to be managed.

“—look at nature and find a production system which mimics nature’s model to our commercial and environmental advantage” (McDonough, 2011).

This perspective suggests that a more profound engagement with materials could lead to innovative design strategies that honour their living essence and inherent properties.

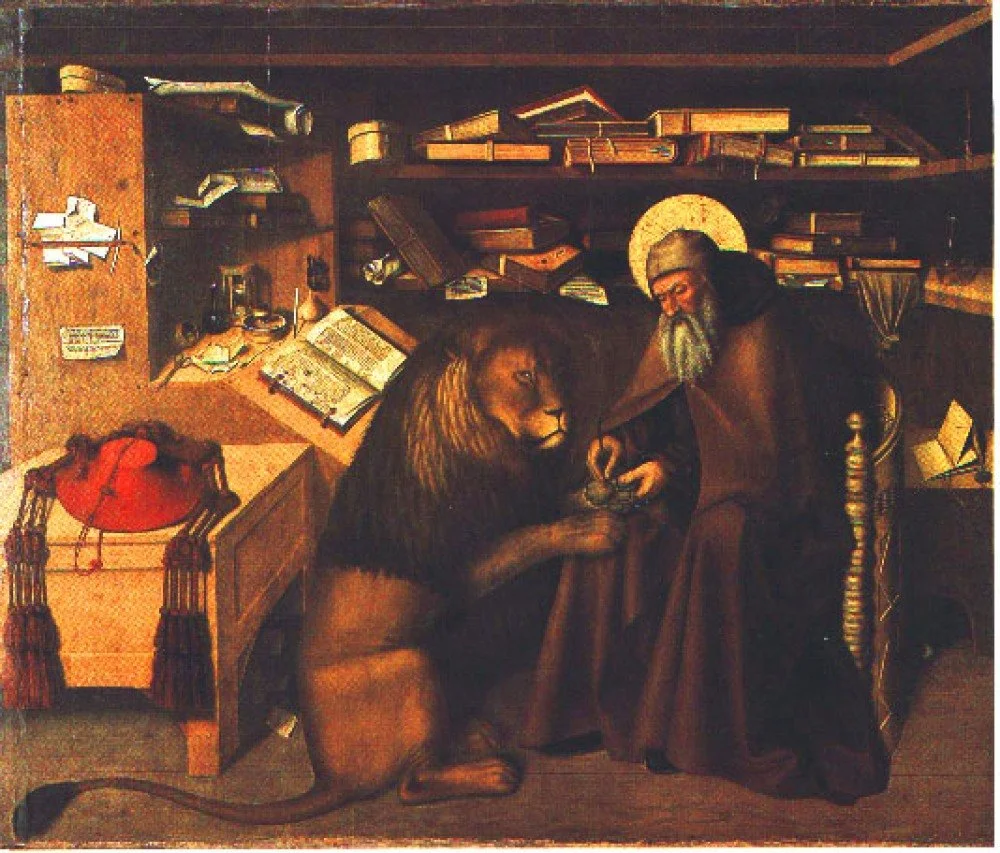

St Jermone and The Lion | Colantonio, 1445

Nature and Culture

The interplay between nature and culture has long been a subject of interest in art and design. Colantonio’s examination of the 1445 painting of St. Jerome and the Lion highlights how art can reflect a dominion over nature, reducing the lion to an object within the space rather than acknowledging its wildness. The lion, painted to blend into the environment, becomes a background element that emphasizes the figure of St. Jerome rather than the lion’s natural presence.

“The encroachment of the animal into the indoor, human space of Jerome's study seems to blur the traditional opposition between the concepts of 'nature' and 'culture'” (Salter, D 2016).

This blending of nature into a constructed environment illustrates how cultural artifacts can both incorporate and dominate natural elements, treating them as commodities rather than living entities.

This perspective can be extended to architectural design, where nature is often subordinated to human intentions. The portrayal of nature as a background element in art reflects a broader tendency in architecture to view natural processes as secondary to human design needs. Understanding how art and architecture have historically treated nature as a backdrop can provide insights into how contemporary practices might better integrate and respect natural processes.

Croft Lodge: Case Study 01

Croft Lodge represents a unique case in understanding and working with decomposing matter. The project, led by Stephenson and Wilson, was not primarily driven by sustainability goals but by an intention to preserve the entirety of the building, including elements often overlooked.

“We decided that everything was equally valuable about it, we wanted to preserve everything, not just the timber which is normally what is considered valuable. Even the cobwebs and the ivy” (Stephenson, J and Wilson, R. 2019).

This approach highlights a shift from conventional conservation methods, which typically focus on preserving what is deemed valuable, to a more holistic view that values all aspects of the building, including its decaying components.

“What is to be done with the huge stock of existing buildings that have outlived the function for which they were built?” (Stone, S. 2020). This question reflects a growing recognition of the need to engage with buildings as dynamic entities rather than static objects. By embracing the decomposition process as part of the design and conservation strategy, Croft Lodge offers a model for how architects can work with the natural life cycle of materials.

Contrasting this approach, American botanist J.H. Wandersee’s concept of “Plant Blindness” explores how humans often overlook the importance of plants and their role in our environment.

“There is a recognized tendency, even for knowledgeable biologists, to overlook, underemphasize, or neglect plants” (Wandersee, Schussler, 1999).

This phenomenon can be extended to architectural design, where the complexity of materials and their interactions with their environment may be underestimated or ignored. By acknowledging the semi-living nature of materials and their symbiotic relationships with their surroundings, architects can develop a deeper understanding of how to incorporate decay and renewal into their designs.

Croft Lodge Studio | KDA Architects

Croft Lodge Studios | KDA Architects

Harmonia 57: Case Study 02

The evolution of modern cities has often been characterized by a division between the ‘natural’ and the urban environment. This separation leads to a fragmented and superficial integration of nature into urban design. Harmonia 57 by Triptyque challenges this dichotomy by aiming to operate as a living organism. The building incorporates irrigation systems and porous openings that allow plants to grow and interact with the structure.

“The water is perpetually recycled, working to ‘mist’ the outside and inside to eventually encase the entire building in biodiversity” (Triptyque, 2020). This approach seeks to blur the boundaries between the built environment and natural processes, creating a more integrated and responsive architectural system.

Despite these innovative strategies, issues persist with unsustainable materials and a superficial application of nature within the design. The approach can be seen as an attempt to address ecological concerns without fully understanding the complexity of biological processes.

“The innate cumbersomeness and inertness of conventional construction materials and systems, which block any real engagement with ecological processes, is to be overturned by chemical innovations of synthetic biology” (Castle, 2011).

This statement highlights the limitations of traditional materials and systems in engaging with ecological processes and suggests that a deeper integration of biological principles is needed for truly regenerative design.

Harmonia 57 | Triptyque Architects

Value of Attention in Material Decay

The importance of decay in materiality and its potential for further investigation at the point of destruction is often overlooked in architectural practice. Ignoring the regenerative potential of decay limits architects' understanding of sustainable cycles and reduces nature to a mere commodity within the production system.

“If the imperative is to limit ‘wet’ trades as much as possible and build with ‘dry’ prefabricated elements that ‘click’ together, the skill sets of site operatives have been emaciated to almost nothing” (Spiller, 2011).

This emphasis on prefabricated elements and dry construction techniques often neglects the rich, dynamic interactions that occur during the decay and renewal processes. By engaging with these processes, architects can gain valuable insights into sustainable design practices and develop a more nuanced approach to materiality.

Regenerative Design and Metamorphosis

Starling’s ShedboatShed project exemplifies the potential for design to engage with the metamorphosis of materials and objects. By dismantling a wooden shed, redesigning it as a boat, and then reassembling it as a shed, Starling explores the lifecycle and transformation of materials.

“Starling’s work might have developed towards analyzing the loss and the gain of material, microbiology, structure, etc.” (Starling, 2020). This project demonstrates how the process of transformation can provide insights into the material's nature and its interactions with its environment. It emphasizes the importance of viewing materials not as static entities but as dynamic, evolving components of design.

Starling’s approach parallels Eames’s Powers of Ten, which illustrates the value of shifting our perspective to understand the broader context of materials and their interactions with the natural world. When decay and cycles are viewed as integral to the design process, we gain a greater appreciation for their necessity and potential.

ShedBoatShed | Tate Modern | Simon Starling

Between Temporary and the Transitional States of Decay

The concepts of temporary, transitional, and permanent decay present intriguing questions about the nature of materials and their lifecycle. Bunschoten’s Spinoza’s Garden and Julie Brook’s Fire Stacks explore these themes by studying the elemental forces at play in the decay and renewal processes.

“The reeds dehydrate the soil. The newly exposed object disappears again among the stems of the reeds and wildflowers” (Bunschoten, 1986). This observation highlights the interplay between decay and growth, illustrating how materials and objects can transition through various states and interact with their environment.

By examining these transitional states, architects can gain insights into how materials can be designed to accommodate and respond to their natural cycles. This approach offers a more nuanced understanding of how to integrate decay and renewal into the architectural process, moving beyond simplistic views of materials as static objects.

Spinoza's Garden | AA Files | No. 11 Spring, 1986

Conclusion

The examination of materiality and decay through case studies like Croft Lodge, Harmonia 57, and Starling’s ShedboatShed reveals the complexities and potential of working with materials as dynamic, living entities. By embracing the regenerative nature of decay and engaging with the biological cycles of materials, architects can develop more sustainable and responsive design practices. This perspective challenges traditional views of materials as static commodities and offers a more nuanced approach to integrating nature and culture in architectural design.

References

BBC Four HD Forest Field and Sky Art out of Nature (Complete Episode) (2016) (2016) Forest, Field and Sky: Art out of Nature. BBC. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XgPQpGeqOkU (Accessed: October 25, 2022).

Burke, A. and Nilsson, F. (2019) “Prototyping Practice,” in M.U. Hensel (ed.) The Changing Shape of Architecture. New York, NY: Routledge, pp. 22–30.

Bunschoten, R. (1986) “Spinoza's Garden,” The AA Files, (11), pp. 1–112.

Castle, H. (2011) “Editorial,” Architectural Design: Protocell Architecture, 81(2), pp. 5–5. Available at: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/ad.1205.

Colantonio, N.A. (1445) “Saint Jerome and The Lion.” Naples, Italy: Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte.

Coleman, N. (2020) “Pool and Cave: Zumthor's Thermal Baths At Vals (1996),” in Materials and meaning in architecture: Essays on the bodily experience of buildings. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, pp. 92–115.

McDonough, W. and Braungart, M. (2009) Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Thing. London: Vintage.

Myers, W. (2018) Bio design: Nature, Science, Creativity. New York: The Museum of Modern Art.

Power of Ten (1977) YouTube. Eames Office. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0fKBhvDjuy0 (Accessed: November 10, 2022).

Salter, D. et al. (2016) “Redeeming the Decadent City: Changing Responses to the Urban and Wilderness Environments in the Lives of St Jerome,” in Romancing Decay: Ideas of Decadence in European Culture. New York: Routledge, pp. 1–16.

Spiller, N. (2011) “Protocells: The Universal Solvent,” Architectural Design, 81(2), pp. 60–67. Available at: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/ad.1205.

Stephenson, J. and Wilson, R. (2019) Croft Lodge Studio by Kate Darby and David Connor, YouTube. YouTube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=egS-hxLngXc (Accessed: November 2, 2022).

Stone, S. (2020) Undoing buildings: Adaptive Reuse and Cultural Memory. New York; London: Routledge, Taylor et Francis Group.

Wandersee, J.H. and Schussler, E.E. (1999) “The American Biology Teacher,” Preventing Plant Blindness, 61(2), pp. 82–86. Available at: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/4450624.

Tate Britian and Curtis, P. (2012) Simon Starling will create the Tate Britain Commission 2013 – press release, Tate . Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/press/press-releases/simon-starling-will-create-tate-britain-commission-2013 (Accessed: November 10, 2022)

Tryptique, T. (2015) Harmonia 57, Area. Available at: https://www.area-arch.it/en/harmonia-57/ (Accessed: December 8, 2022).

Wooden Structure, Horse Chestnut (2022).